AFTER THE MELT: Climate change and Idaho’s Snake River

story by MARY ANN REESE

photos by Idahostockimages.com

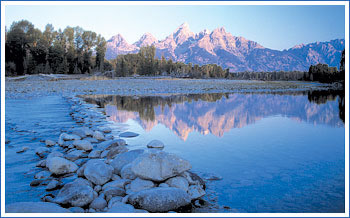

How will climate change impact Idaho’s

Snake River water supply?

THAT’S THE QUESTION Russ Qualls, Idaho’s climatologist, is asking in lengthy studies involving water that feeds southern Idaho’s Snake River Plain (SRP). The SRP could gain “some benefit” from potential climate change during the next 20 to 70 years, Qualls told Idaho legislators in February.

photo©IDAHOSTOCKIMAGES.COM

The Snake River Plain averages just 10 to 12 inches precipitation a year, so most irrigation water supplying Idaho’s $5.6 billion-a-year agricultural industr y must come from the mountains. Central and northern Idaho mountains historically average 30 to 80 inches of precipitation a year, moisture entering the river system downstream from the SRP.

Teton, Sawtooth snows feed SRP

Snowmelt runoff feeding the SRP comes mainly from the Tetons on the Idaho/Wyoming border and the southern Sawtooths via the Big Wood, Boise, and Payette rivers.

Qualls, also associate professor with UI’s Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering, worked with university economists Gar th Taylor and Joel Hamilton. They fed 25 years of snowpack and temperature data from both the Tetons and Sawtooths— from 1981 through 2006—into computer models to estimate snowmelt runoff and irrigation water allocation. Then they modified historical data with six possible scenarios to predict the potential range of impacts on the Snake River water supply by years 2030 and 2080.

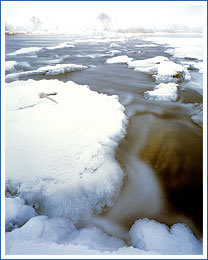

“Results suggest we could end up with some small benefit from climate change,” says Qualls. Many climate models indicate the Nor thwest may get warmer and wetter. As a result, four of six scenarios predict 0.5 to 20 percent increases of water flowing into the Snake. The two driest scenarios suggest a 2 to 5 percent water reduction. All results showed runoff occurring 5 to 8 days earlier in the spring than present runoff.

photo©IDAHOSTOCKIMAGES.COM

Legislature funds water capacity studies

Qualls’ studies suppor t what state leaders already know, that Idaho needs to do more to replenish aquifers and increase sur face water storage capacity.

At his 2007 Water Summit, Gov. C.L. “Butch” Otter challenged Idahoans to develop a long-term vision for addressing existing and looming surface and ground water supply conflicts. The 2008 Legislature responded by funding $1.8 million to consider enlarging Minidoka Dam and replacing Teton Dam and $20 million over the next decade to plan and manage Idaho’s major aquifers.

Hal Anderson, Boise, head of planning for the Idaho Department of Water Resources, said other climate change studies forecast potential shortages, given runoff changes and extended droughts. He praised Idaho legislators for the funding. He observed it isn’t just climate change “but also a growing Idaho population, conjunctive use of surface and ground water, and endangered species” affecting Idaho water demands.

The federal government must provide water for endangered salmon, another need for Snake River water. While some 95 percent of Snake River water and 60 percent of Idaho groundwater now go to agriculture, Anderson foresees urban areas growing and having both greater needs and greater ability to pay to get water as supplies tighten. “It is good that we can move ahead with this important planning,” said Anderson.

Meanwhile, Qualls’ studies continue.

Contact Russ Qualls at rqualls@uidaho.edu.

|